Filters » Low-pass filters

Low-Pass Filters

A low-pass filter is a circuit offering easy passage to low-frequency signals and difficult passage to high-frequency signals. There are two basic kinds of circuits capable of accomplishing this objective, and many variations of each one: The inductive low-pass filter is shown in following figure.

FIGURE

The inductor's impedance increases with increasing frequency. This high impedance in series tends to block high-frequency signals from getting to the load.

FIGURE

The capacitive low-pass filter is shown in the following figure.

FIGURE

The capacitor's impedance decreases with increasing frequency. This low impedance in parallel with the load resistance tends to short out high-frequency signals, dropping most of the voltage across series resistor Ra.

FIGURE

The inductive low-pass filter is the pinnacle of simplicity, with only one component comprising the filter. The capacitive version of this filter is not that much more complex, with only a resistor and capacitor needed for operation. However, despite their increased complexity, capacitive filter designs are generally preferred over inductive because capacitors tend to be "purer" reactive components than inductors and therefore are more predictable in their behaviour. The term "pure" here means that, capacitors exhibit little resistive effects than inductors, making them almost 100% reactive. On the other hand, inductors typically exhibit significant dissipative (resistor-like) effects, both in the long lengths of wire used to make them and in the magnetic losses of the core material. Capacitors also tend to participate less in "coupling" effects with other components (generate and/or receive interference from other components' via mutual electric or magnetic fields) than inductors, and are less expensive.

However, the inductive low-pass filter is often preferred in AC-DC power supplies to filter out the AC "ripple" waveform created when AC is converted (rectified) into DC, passing only the pure DC component. The primary reason for this is the requirement of low filter resistance for the output of such power supply. A capacitive low-pass filter requires an extra resistance in series with the source, whereas the inductive low-pass filter does not. In the design of a high-current circuit like a DC power supply where additional series resistance is undesirable, the inductive low-pass filter is the better design choice. On the other hand, if low weight and compact size are higher priorities than low internal supply resistance in a power supply design, the capacitive low-pass filter might make more sense.

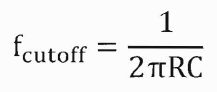

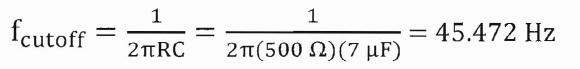

All low-pass filters are rated at a certain cut-off frequency i.e., the frequency above which the output voltage falls below 70.7% of the input voltage. This cut-off percentage of 70.7 is not really arbitrary, all though it may seem so at first glance. In a simple capacitive/resistive low-pass filter, it is the frequency at which capacitive reactance in ohms equals resistance in ohms. In a simple capacitive low-pass filter (one resistor, one capacitor), the cut-off frequency is given as:

FIGURE

When dealing with filter circuits, it is always important to note that the response of the filter depends on the filter's component values and the impedance of the load. If a cut-off frequency equation fails to give consideration to load impedance, it assumes no load and will fail to give accurate results for a real-life filter conducting power to a load.

One frequent application of the capacitive low-pass filter principle is in the design of circuits having components or sections sensitive to electrical "noise." As mentioned at the beginning of the last chapter, sometimes AC signals can "couple" from one circuit to another via capacitance (Cstray) and/or mutual inductance (Mstray) between the two sets of conductors. A prime example of this is unwanted AC signals (noise) becoming impressed on DC power lines supplying sensitive circuits.

FIGURE

The oscilloscope-meter on the left shows the "clean" power from the DC voltage source. After coupling with the AC noise source via stray mutual inductance and stray capacitance, the voltage as measured at the load terminals is now a mix of AC and DC, the AC being unwanted. Normally, one would expect Vload to be precisely identical to Vsource, because the uninterrupted conductors connecting them should make the two sets of points electrically common. However, power conductor impedance allows the two voltages to differ, which means the noise magnitude can vary at different points in the DC system.

If we wish to prevent such "noise" from reaching the DC load, all we need to do is connect a low-pass filter near the load to block any coupled signals. In its simplest form, this is nothing more than a capacitor connected directly across the power terminals of the load, the capacitor behaving as a very low impedance to any AC noise, and shorting it out. Such a capacitor is called a decoupling capacitor.

FIGURE

A cursory glance at a crowded printed-circuit board (PCB) will typically reveal decoupling capacitors scattered throughout, usually located as close as possible to the sensitive DC loads. Capacitor size is usually 0.1 or more, a minimum amount of capacitance needed to produce a low enough impedance to short out any noise. Greater capacitance will do a better job at filtering noise, but size and economics limit decoupling capacitors to meagre values.